Downtown Denver is changing fast. The city approved a new 20-year plan to revive the area, and one big move stands out: turning empty office buildings into housing. Because of this shift, every developer now needs a fresh traffic study before starting any design work. Many older reports no longer match the city’s new goals, especially with mobility, street use, and access rules changing throughout the downtown core.

Denver leaders want a downtown that feels alive again. They want more people living, walking, biking, and using public spaces—not just commuting in and out. This sounds exciting, but it also creates new challenges. Converting an office tower into homes is not a simple swap. Traffic patterns change, street needs change, and site access changes. So developers need clear engineering guidance early, or the project could face long delays.

Denver’s New Downtown Plan Pushes for Big Shifts

Over the last few years, downtown Denver struggled with high office vacancies. Remote work left many buildings half-full or completely empty. This pushed the city to rethink how the area should function over the next two decades.

The new Downtown Denver Area Plan focuses on turning unused offices into housing, improving sidewalk and bike connections, strengthening transit access, and creating more public spaces. It also aims to boost safety, encourage mixed-use areas, and support a stronger local economy.

This shift affects developers right away. When a building changes use—from office to residential—the city treats it like a brand-new project. That means new requirements, new reviews, and new mobility expectations. And it all starts with transportation.

Why Office-to-Housing Conversions Change Traffic Completely

Office buildings bring a specific type of traffic. Workers arrive at the same time in the morning, leave in the evening, and travel mostly by car or transit. Housing brings the opposite. Residents come and go all day. They need different access points, different parking setups, and different safety measures.

Because of this, the city wants updated information before approving any design.

Trip patterns look different. Office workers create clear peak hours, while residents move in waves—mornings, afternoons, nights, weekends. Denver wants to understand how this mix affects nearby streets and transit stops.

Parking needs to shift as well. Office buildings rely on daytime parking, but housing needs 24/7 parking, bike storage, safe pick-up areas, and ADA paths. Loading docks that worked for office deliveries may not support residential living.

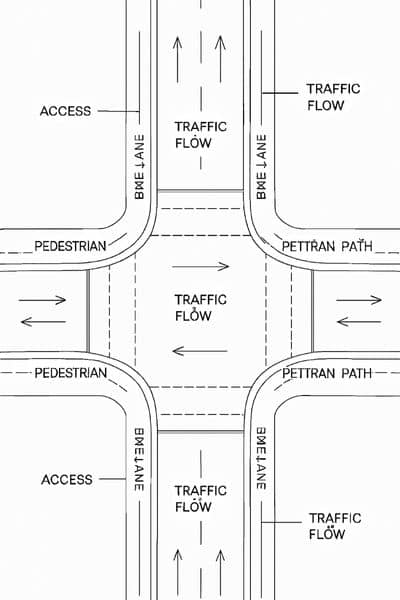

Access points may change because downtown streets are evolving. New bike lanes, redesigned sidewalks, and protected crossings affect how cars, bikes, and pedestrians move around the site. Old reports don’t match new mobility priorities, so design teams need the correct data.

That is why a fresh traffic study matters. It protects the project, the timeline, and the budget.

How a Traffic Study Helps Developers Avoid Costly Surprises

Many developers skip straight to concept design. They want renderings, unit counts, and budgets right away. But skipping the traffic study can create huge risks. When engineers check access and mobility first, they prevent issues that can derail the whole project.

A traffic study shows whether a site even works for housing. Some buildings sit on narrow streets that limit access. Others have alleys that cannot support emergency vehicles, trash pickup, or deliveries. Identifying this early saves time and money.

The study also guides the design team by mapping out driveway locations, sidewalk improvements, bike access, emergency routes, pick-up and drop-off areas, and lighting needs. With the right information, designers make smart choices. Without it, they guess and end up redesigning everything later.

It also speeds up city reviews. Denver now prioritizes walkability, safety, and multimodal access. If the traffic study supports the project’s mobility plan, reviewers move faster because the design matches the city’s new goals.

Most of all, the traffic study prevents major redesigns. If the team discovers access issues after drawings are complete, the whole layout may need changes. Parking levels, retail spaces, lobby entrances, and mechanical rooms all depend on access points. Early traffic data eliminates these painful surprises.

A Realistic Example: Turning a 1980s Office Into Housing

Imagine a developer buying a mid-rise office building on a block where a new bike lane and bus upgrade are planned. The old traffic report shows car-heavy commuter patterns. But Denver’s new plan focuses on walking and transit. This mismatch creates big risks.

The engineer checks nearby streets, bike lanes, and transit stops. They find that the alley behind the building cannot support new residential loading needs. They also spot a planned lane reduction that will affect vehicle access.

Next, the engineer runs a fresh traffic study. The results show that the main access point must shift 40 feet to meet new safety rules. The design team adjusts the lobby entrance, parking layout, and bike storage areas based on these findings. When the project reaches city review, it matches the new mobility plan. The city approves it faster, and the developer avoids months of delays.

This example shows how early traffic work protects the entire project from uncertainty.

Developers Win When They Start With Mobility First

Denver wants a downtown that feels safe, connected, and easy to move through. Developers who understand this new direction gain an edge. They spot issues earlier, design smarter, and avoid delays that raise project costs.

Developers who plan ahead now order traffic studies before buying buildings. They know that land use changes shift mobility needs. They bring civil engineers into the project early instead of halfway through design. And they shape projects that support future vision, not the past.

These choices save money, reduce stress, and help create a downtown that works for people who live, walk, and enjoy the city every day.

Conclusion:

Office-to-housing conversions offer major opportunities. But the path is not simple. Streets are shifting, mobility rules are tightening, and the city now reviews traffic with more detail than ever.

A fresh traffic study acts as the foundation. It shows what works, what doesn’t, and what needs to change before design even begins. When developers make this the first step, they move faster, avoid redesigns, and set their projects up for success.

Denver’s next chapter is starting now. Developers who plan their mobility strategy first will lead the way.